DIO (Do It Ourselves)

Boston, Massachusetts / Spring 2022 / Near-Future City Core 4 Studio / Critic Danielle Choi / Systems Design, Infrastructure, Urban Tree Canopy, Design Justice

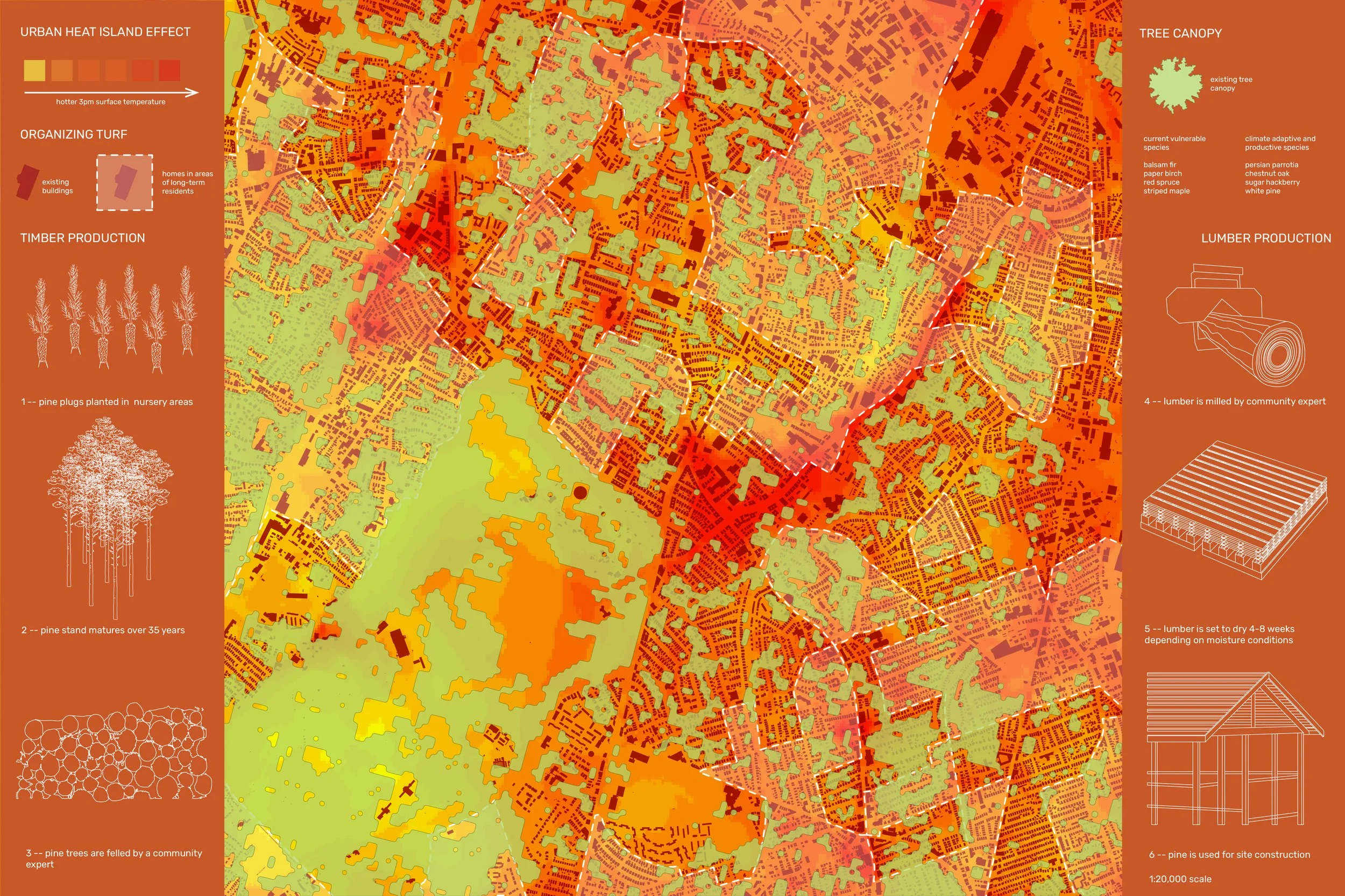

Neighborhood model tracks changes to the designer-organizers' “turf” or site. Used to communicate with nearby designer-organizers to track regional planning.

DIO is a project and practitioner model that translates community ideas into urban space, piloting how a neighborhood can self-determine its own design. A new practitioner, the designer-organizer, coordinates code changes and designs a productive and climate-adaptive tree canopy to combat urban heat island effect. The species are adapted to warmer weather and include millable pines that are later transformed into lumber for neighborhood construction projects. The project constructs neighborhood power, enabling residents to add density to their triple-deckers and build wealth to fight displacement and gentrification. In a near-future city, DIO operates as an enduring model able to propagate just spatial practices and affect the collective and immediate needs of the urban landscape.

Map details heat risk to Grove Hall, existing tree canopy coverage and zones of high renter + owner occupancy. Margins outline the pine production process.

Grove Hall is a residential neighborhood facing extreme heat, stormwater flooding risk and the threat of displacement, conditions endemic to much of Boston. Transitioning the neighborhood to a resilient and self-determined community is coordinated by a new type of practitioner, a designer-organizer. The designer-organizer works across multiple scales to coordinate policy with local implementation; build consensus through visualization; and prototype design concepts through scenarios. Embedded in the community it's leading, the designer-organizer builds community power to ensure neighbors have agency in the future of their streets through the Do It Ourselves (DIO) model.

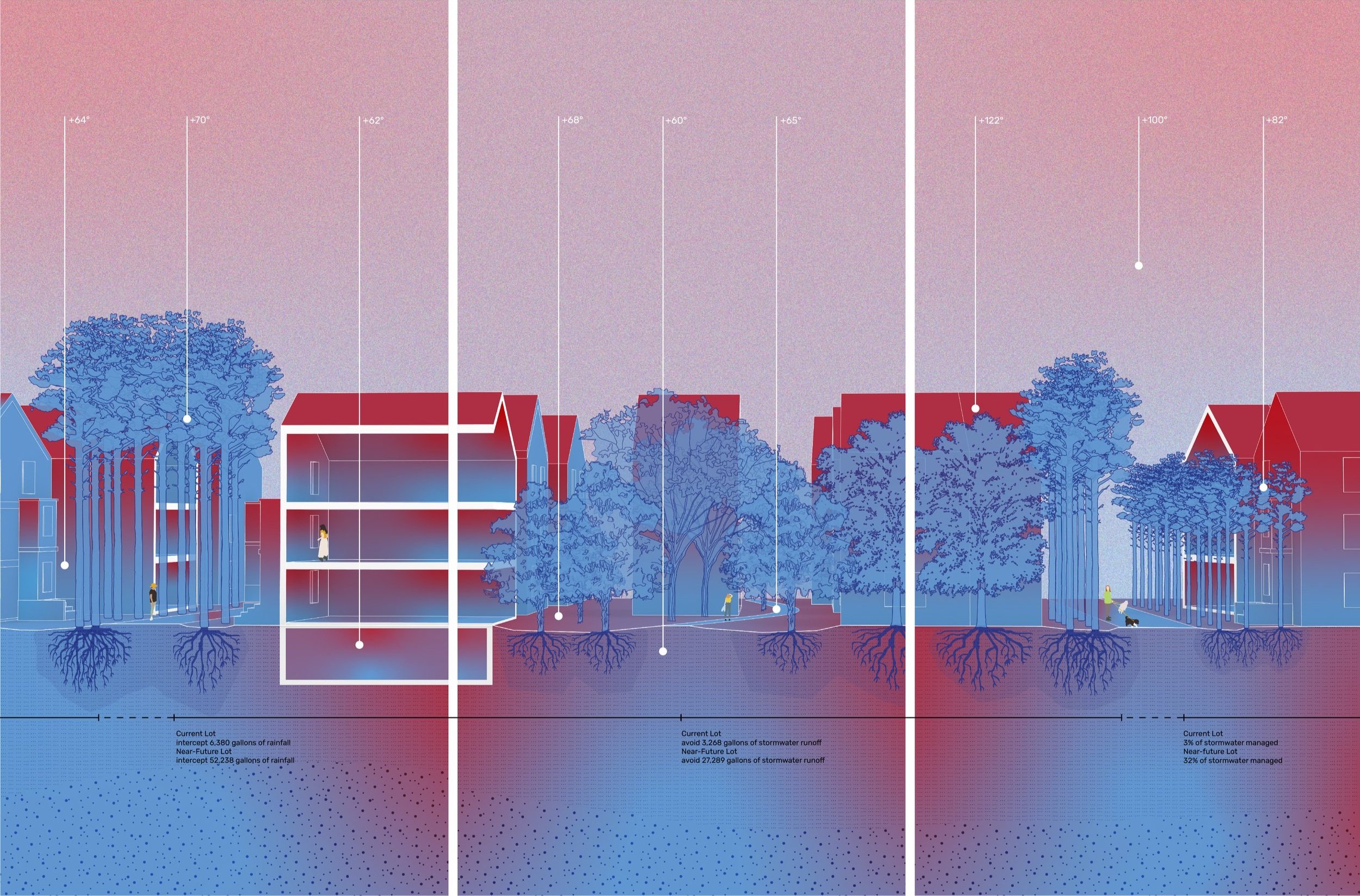

Section details surface temperatures in the near-future with the growing canopy. The reduced pavement and root systems provide significant on site stormwater infiltration.

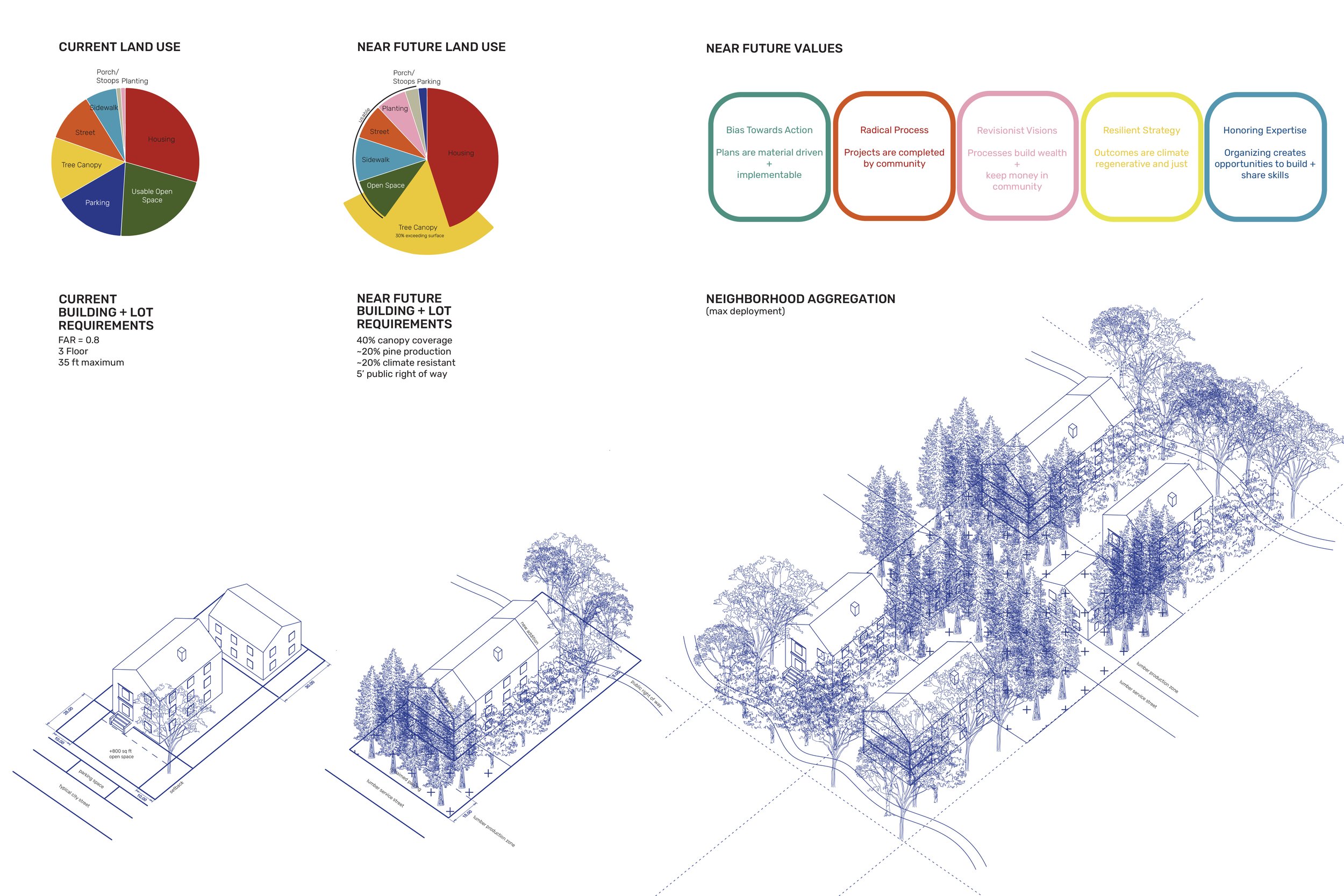

3D code diagram illustrates the transition from dimensional restrictions to tree coverage policy at a single and neighborhood aggregation. Five near-future values guide the DIO model.

The designer-organizer is lead by five values:

Bias Towards Action: plans are material-driven and implementable

Radical Process: projects are completed by community

Revisionist Visions: processes build wealth and keep money in community

Resilient Strategy: outcomes are climate regenerative and just

Honoring Expertise: organizing creates opportunities to build and share skills

DIO weaves in existing policy with new codes and is initiated by the city deeding sidewalks and parking spaces to homeowners, responding to standardized car sharing in the near future. The design-organizer works to pass new code that removes setbacks, and without on-street parking, housing lots are expanded by 15’. Public rights of way become flexible and coordinated between neighbors and are responsive to local topography. Traditional front yards, once tied to the city street, are flipped to the back of the houses, creating a neighborhood-wide “porch” for more explicit communal space. City streets are transformed into pine production throughways for lumber manufacturing that supply neighborhood densification projects.

Residential projection illustrates the three typologies to alter ownership and add density to triple deckers. Neighborhood zones are established for commons and pine growing and production areas with distinct species.

1”:50’ Model

The tree canopy is planned in concert with the city and designer-organizer and is all climate-adaptive species which together reduce heat island effect, cooling surfaces 15 degrees on hot summer days. The enriched urban forest provides significant on-site stormwater infiltration. Half of the new trees are pines and are managed for lumber production. Once mature, the pine is harvested and used for construction. The vernacular triple-deckers are expanded and connected to create new units to accommodate the area's growing population. The new units increase property values and provide income, and add more residents to the community. Grove Hall is a diverse neighborhood, and as families expand they are able to live together as the buildings grow.

DIO model framework illustrates the relationships and functions of the designer-organizer and residents over time. The model accounts for spatial and policy changes and municipal and neighborhood governance, as well as financial and ecological benefits.

Tufted and 3D printed models show a possible tool that designer-organizers can deploy to engage with neighbors, exploring design options for additions and planting plans.

Timeline shows neighborhood changes over time as the hardscaping is removed and tree canopy matures. Material flows are coordinated to support build efforts in the neighborhood.

Community workdays, hosted by the designer-organizer, include tree planting, harvesting, and framing days. Neighborhood captains--those with construction experience--lead building projects, accompanied by future captains in training. Expertise is shared and over time as neighborhood capacity is built for more complex and longer-term projects. New forms of representation and models are used by the designer-organizer to visualize and build consensus for neighborhood changes.

Groundfloor cutaway shows the neighborhood activated with residents and their various roles and plans for the future.

1”:30’ Models

DIO is underpinned by the designer-organizer, who works to build power in the neighborhood through designing resilient neighborhood relationships for a more just near-future. Ultimately, the project is a recalibration of the role of a landscape architect to the urgency of changing climate, framing the practitioner as a leader and advocate for more just ways to live.